An article by Diamond and Kaul in the American Journal of Cardiology outlines additional difficulties for the science of medical predictions.

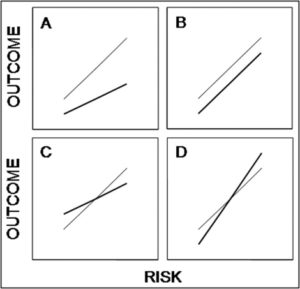

Some of the problems related to HTE have been outlined by Kravitz et al., as we have previously seen, and Kent et al. offered a proposal to mitigate them. But as we noted, the proposal by Kent et al. assumes a treatment that provides fixed relative risk reduction across the range of risks. This is displayed in Panel A in the AJC paper:

The thin line is the hypothetical baseline risk-outcome relationship, the bold line is the post-treatment risk-outcome relationship. In Panel A, the relative risk reduction is constant. As one moves from lower risk to higher risk, the absolute benefit (vertical difference between the lines) increases.Continue reading “Heterogeneity of treatment effect: additional difficulties”