[This is the transcript of a paper I presented at the Austrian Economics Research Conference at the Mises Institute. I have included the slides below and you can hear the audio here. The title of the paper is “From reacting machine to acting person: a praxeological interpretation of the patient, his health, and his medical care.” For more info on praxeology, see my previous article here. I have split the presentation into two parts. This is a very condensed talk, covering a lot of ground, but I will elaborate on various points I make in the paper in the ‘progress notes’ section of this website over the next few days and weeks. Thank you for reading and for any feedback you might have.]

The elephant in the room in healthcare is that there is no precise definition of health. I believe that this ambiguity plays a major role in our perennial healthcare crises, and I am hopeful that Austrian insights can be helpful.

Here is the outline of my talk.

I will first identify the two dominant modes of thinking about health in modern Western societies. I will show that those conceptual modes are counterproductive to fostering health, both economically and medically. I will then propose a praxeological interpretation of health, and sketch the possible benefits and ramifications of that interpretation.

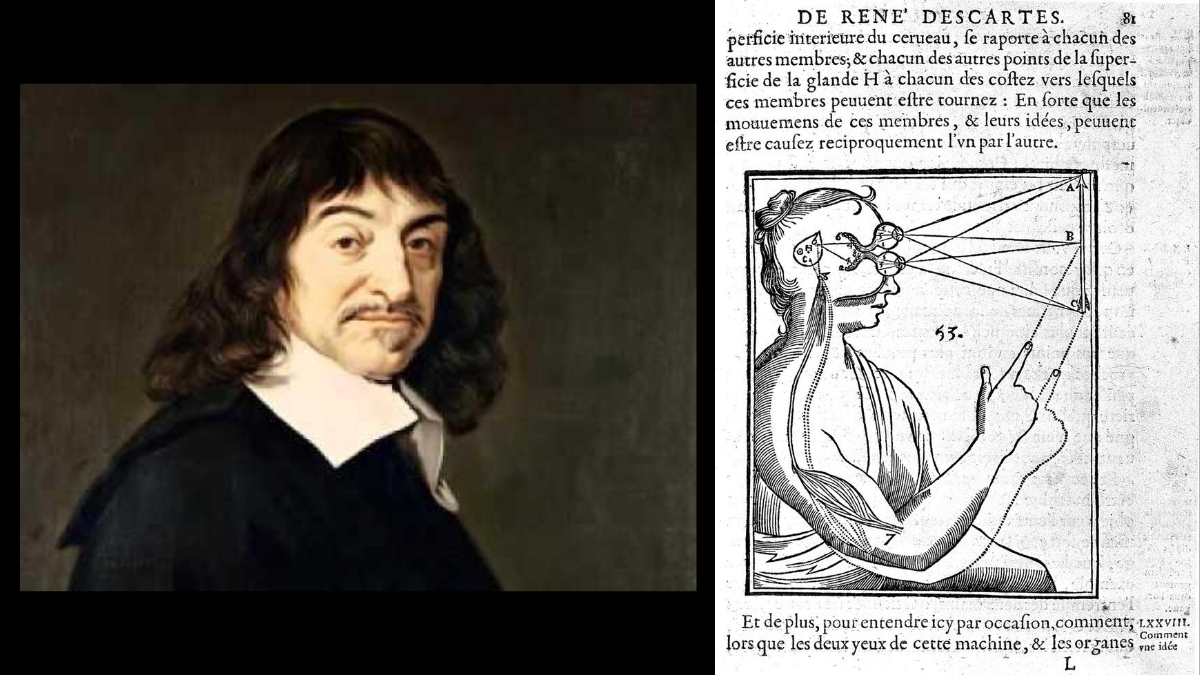

The dominant mode of thinking about health in Western societies owes its origins to René Descartes who, at the beginning of the scientific revolution, proposed the machine concept of the organism. Descartes’ proposal was a radical departure from pre-existing notions which were rooted in the idea that organisms have essences and natures. Instead, he proposed that every material body is an assemblage of tiny particles moving mechanically according to physical laws. In the case of plants and animals, God directs the laws and the motions. In the case of humans, the mechanical bodies are under the control of a separate human soul acting like a “ghost in the machine.”Continue reading “From reacting machine to acting person – part 1”

The dominant mode of thinking about health in Western societies owes its origins to René Descartes who, at the beginning of the scientific revolution, proposed the machine concept of the organism. Descartes’ proposal was a radical departure from pre-existing notions which were rooted in the idea that organisms have essences and natures. Instead, he proposed that every material body is an assemblage of tiny particles moving mechanically according to physical laws. In the case of plants and animals, God directs the laws and the motions. In the case of humans, the mechanical bodies are under the control of a separate human soul acting like a “ghost in the machine.”Continue reading “From reacting machine to acting person – part 1”