To summarize W’s case up to March 17, here were the salient features:

- Baseline signs of conduction system disease

- Progressive, and now severe, dyspnea on exertion

- Unexplained relative hypotension, not due to adrenal insufficiency

- Weight loss and early satiety

- Hypercalcemia, initially mild, now more pronounced, with suppression of PTH

- Markedly active urinary sediment with severe dipstick proteinuria, but also microscopic hematuria and calcium oxalate stones

- Worsening renal function, possibly pre-renal azotemia.

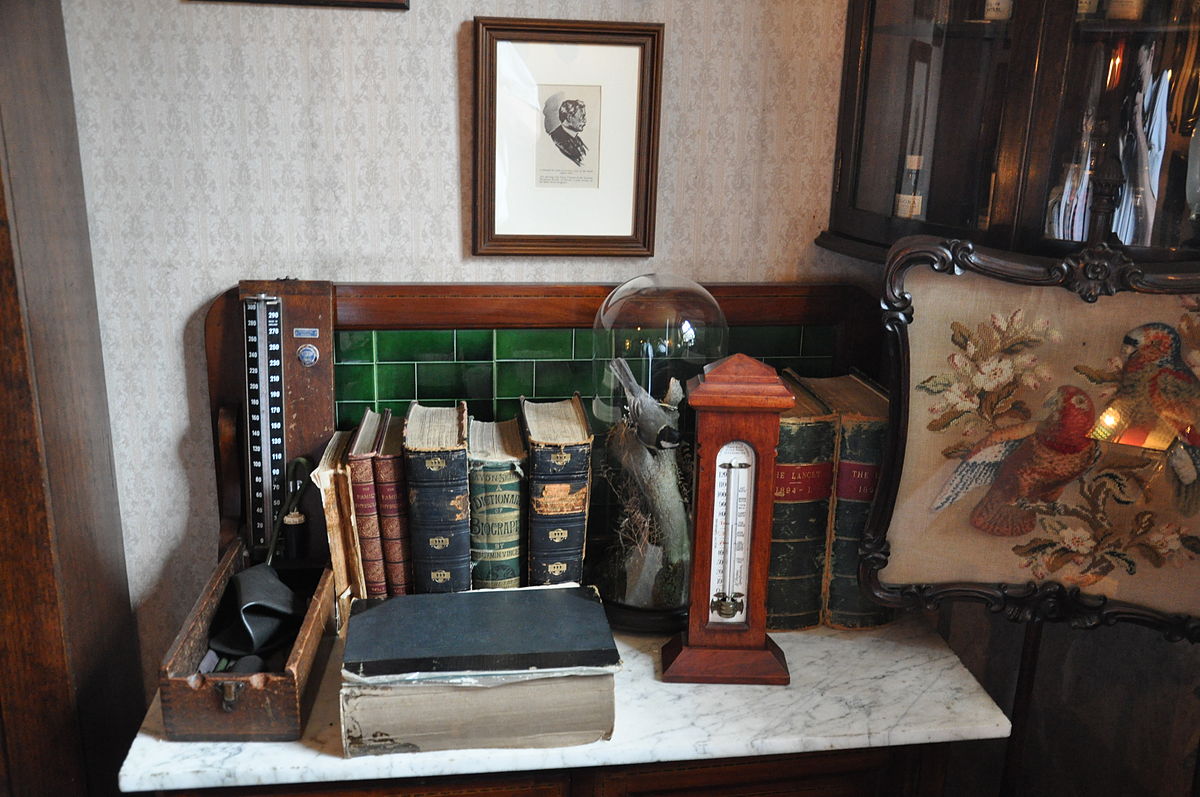

The 50-mile distance separating W from my office made frequent visits impractical, but from March 17 onward I was essentially on daily contact with the patient either by phone or email.

I could not tie everything together, but the thought occurred to me that he might have systemic sarcoidosis with cardiac involvement: hypercalcemia, heart block, shortness of breath, gastrointestinal symptoms. In fact, I was clearly hoping for this diagnosis as something potentially treatable in what otherwise looked like an ominous illness.

On March 19, however, a 2-view chest x-ray was normal and the light bulb that had gone off in my head a few days before was quickly burnt.Continue reading “From DPC to CPC – part 2”