[This is the wrap-up to the series on the economic history of the American healthcare system, the first installments of which can be found here and here.]

The term “managed care” entered the common lexicon in the 1990’s, when contracted arrangements between physicians and hospitals on the one hand, and insurance entities on the other, became standard means to try to control healthcare expenditures. The origin of the concept is frequently credited to Dr. Paul Ellwood and his influential Jackson Hole Group, who introduced the idea in the early 1970’s.

But in our 2-part series on the economic history of American medicine, we saw that healthcare has been “managed” from its inception in the late 1910’s, when the Flexnerian reforms and the ensuing medical licensing laws began to influence (and limit) the type of medical care Americans could choose to receive.

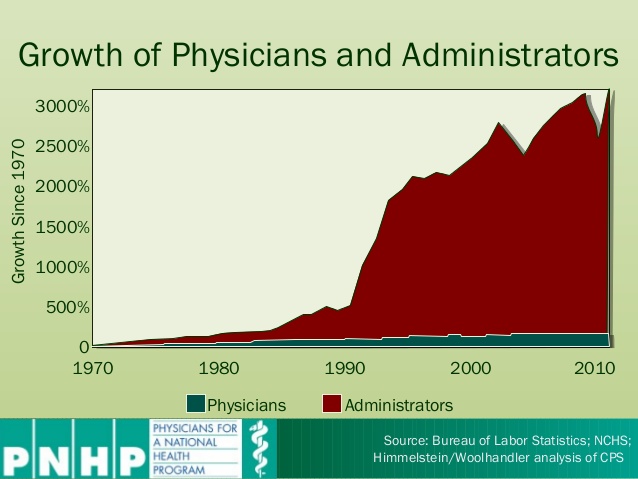

Since that time, an ever-growing managerial class of academics, industry leaders, technocrats, and private foundation believers in “systems” and in a “scientific” approach to organizing society has been guiding the various government interventions which have shaped American healthcare as we know it today.(1)Continue reading “One hundred years of managed care”