A study published a couple of months ago in the BMJ made headlines for claiming that medical errors are the third leading cause of death. As expected, the reactions were swift and polarized.

For some, the study confirmed that the self-serving healthcare system is utterly careless about the welfare of patients. For others, the claim was complete hogwash, based on faulty methodology designed to justify further regulatory oversight.

The two positions are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

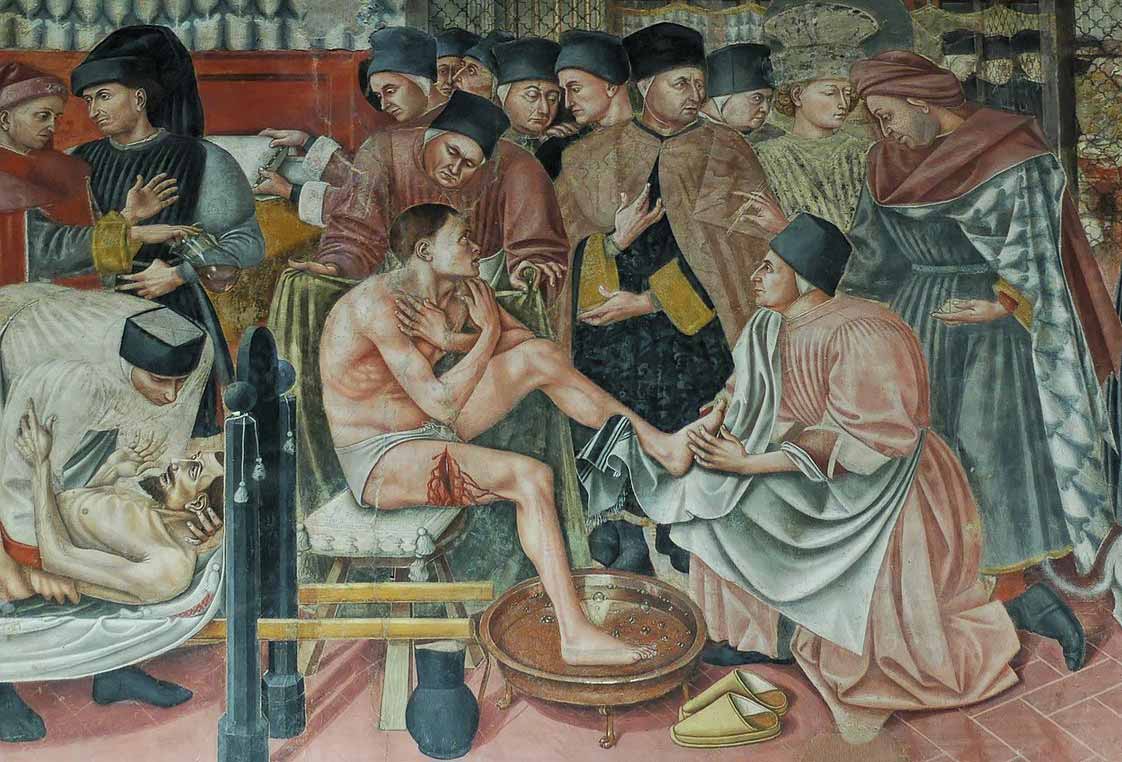

The BMJ study did not come out of the blue. It is simply the latest development in the War on Error which was launched by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) when it published a damning 300-page report entitled To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System.

The effects the IOM report have been two-fold. On the one hand, it gave birth to a highly lucrative patient safety industry. On the other, it has made impossible any sane discussion of iatrogenesis and medical errors. All are now reduced to either confirming or refuting whether a city the size of Miami (or is it the size of Houston?) perishes every year as a result of avoidable harm.

Agreement on what constitutes an error is also seriously lacking. Depending on the research study, the term may refer to innocuous and victimless mistakes retrospectively identified by zealous chart reviewers; unforeseen and likely unavoidable complications of severe and complexes illnesses; systematic flaws in poorly designed workflows; and egregious acts of carelessness. And since the intention of the perpetrators can never be ascertained, outright homicides might conceivably also fall under the category of “error!”

Fortunately, a scholarly book by Virginia Sharpe and Alan Faden, published a year before the IOM issued its report, gives the question of medical abuse and error its proper perspective. Medical Harm: Historical, Conceptual, and Ethical Dimensions of Iatrogenic Illness, offers an in-depth examination of the many facets of iatrogenesis, including its complex moral and philosophical aspects. The first chapters of the book deal with the historical background pertinent to the American healthcare experience.

Chapter one, entitled “Divided loyalties: harm to the profession vs. harm to the patient,” describes the medical landscape in the United States prior to the introduction of licensing laws. It draws attention to the efforts of professional consolidation led by the American Medical Association, whose creation was “a self-conscious strategy on the part of orthodox practitioners to protect and champion their collective interests.”

The 1847 AMA’s Code of Ethics, crafted at the foundation of the organization, was designed to legitimize the AMA’s position as sole representative of the profession. According to Sharpe and Faden, the effectiveness of the Code “can no doubt be accounted for in large part because its more self-serving aims are articulated in and alongside an expansive rhetoric expressing the ideal of patient welfare.”

Among the explicit self-serving aims of the Code were instructions on how to deal with physician deficiency or, perhaps more precisely, on how not to deal with it:

In many passages of the 1847 Code, oblique reference is made to the circumstances of professional disagreement or to the incompetence or deficiency of colleagues. In each passage…discretion and silence are the rule. In consultation, for example, ‘all discussions should be held as secret and confidential. Neither by words nor manner should any of the parties to a consultation assert or insinuate that any part of the treatment pursued did not receive his assent.’ Furthermore, the consulting physician should not make any hint or insinuation that ‘could impair the patient’s confidence in the attending physician or negatively affect his reputation.’ (emphasis mine)

Protecting the reputation of individual members of the organization was an important means by which the reputation of the profession could also be safeguarded. But another reason to neglect a mechanism for dealing openly with incompetence is that the AMA was supremely confident in the value of a scientific education. This confidence was articulated in the Code’s “consultation clause” prohibiting AMA members from including “sectarians” in consultation.

‘No one,’ says the Code, ‘can be considered as a regular practitioner or a fit associate in consultation, whose practice is based on exclusive dogma, to the rejection of the accumulated experience of the profession, and of the aids actually furnished by anatomy, physiology, pathology, and organic chemistry. (p.23)

Over time, the emphasis on scientific expertise would acquire even greater importance and transcend the fight against the heterodox practitioners. With the successes of laboratory science and its application to medicine, proponents of “scientific medicine” would make the claim that science alone is sufficient to guide medical action. Quoting historian J.H. Warner, Sharpe and Faden state that “the most formidable challenge [to the Code of Ethics] came from the advocates of scientific medicine.”

By the 1870’s advocates of experimentally-based medicine dismissed the consultation clause and with it the authority of the Code as a whole, arguing that science alone was the appropriate arbiter in medical matters. According to the Code’s principal detractors, any general distinction between sectarians and regulars was specious and arbitrary, for true science is entirely ‘indifferent to Hippocrates and Hahnemann (the founder of homeopathy). [emphasis mine]

As we saw previously, it is this strand within the AMA that eventually succeeded in promoting the enactment of licensing laws, grounding them in the dubious ethical and epistemological claims of scientific medicine.

The rest, as they say, is history. After passage of the Flexner reforms, and with government-granted privilege to establish “standards of care,” the AMA-led medical profession would gradually distance itself from its Hippocratic principles and all but abandon its traditional emphasis on service to the individual patient.

Armed with powerful scientific and technological know-how, twentieth-century medical paternalism would become a virulent attitude that, to this day, can expose hordes of patients to the consequences—medical and financial—of unnecessary surgeries, unnecessary drugs, and unnecessary hospitalizations.

As it endeavors to reduce the rate of medical errors, the patient safety movement should bear in mind this historical perspective. Medical licensing laws dangerously combine professional self-protection with therapeutic scientism. Unless that fundamental regulatory error is recognized, adding layers of bureaucratic oversight to the practice of medicine will only paper over—or further enable—an epidemic of medical harm unprecedented in the history of mankind.

[Related post: Is medicine a scientific enterprise?]

[Related post: Flexner versus Osler]

[Related post: Are patient safety organization losing the war on error?]

Thank you for this article. I would add that one byproduct of self-preserving AMA is the inability of doctors to ‘go off script’. If your illness/symptoms do not match what is on the list of approved diseases(cancer, heart disease, organ failure etc) then they can’t help you.

I encountered this with my Mother, who has a peculiar physiology. She had an MRI which showed that she had an ’empty Sella’ (flattened pituitary) but for no reason (no tumor etc.).

She was so perplexing to them they didn’t want to see her anymore.So they didn’t. She is in a nursing home now but has none of the official diseases.

You’re right. The rationale behind licensing is one that fosters standardization and has low tolerance for exceptions or unknowns. This has been increasingly a problem over the decades, especially in the age of third-party payment.