My last post was prompted by a reader’s comment where Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning and Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal were juxtaposed. Since receiving that message, I have had occasion to notice that others also associate these two books.

For example, both are mentioned positively in this moving article by Dr. Clare Luz about a friend’s suicide, and in these tweets from Dr. Paddy Barrett’s podcast program:

Must Reads: Man’s Search for Meaning by Victor Frankl. Reread, then reread. Just brilliant! https://t.co/131G3KSYqU pic.twitter.com/zIbAtRsmgU

— TheDoctorParadox (@paradox_doctor) January 2, 2016

Must Reads: Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End by Atul Gawande. Excellent!! https://t.co/ymiDLtqNQH pic.twitter.com/7YHKEr8GSS

— TheDoctorParadox (@paradox_doctor) January 7, 2016

Friends and patients of mine have likewise mentioned these two works to me, expressing praise and testifying to the deep impact the books have had on them.

I suspect that many readers of this blog will at least be familiar with these two books. If not, summaries are here (Frankl) and here (Gawande).

I read the books in succession and found the difference between the two striking. Frankl and Gawande seem to be at polar opposites on the question of life and death. In this post, I will explore this difference, starting with Gawande’s point of departure.

Trajectories of life

In the second chapter of his book, Gawande provides three sketches which, in my opinion, provide the basis of understanding on which the remainder of his book rests.

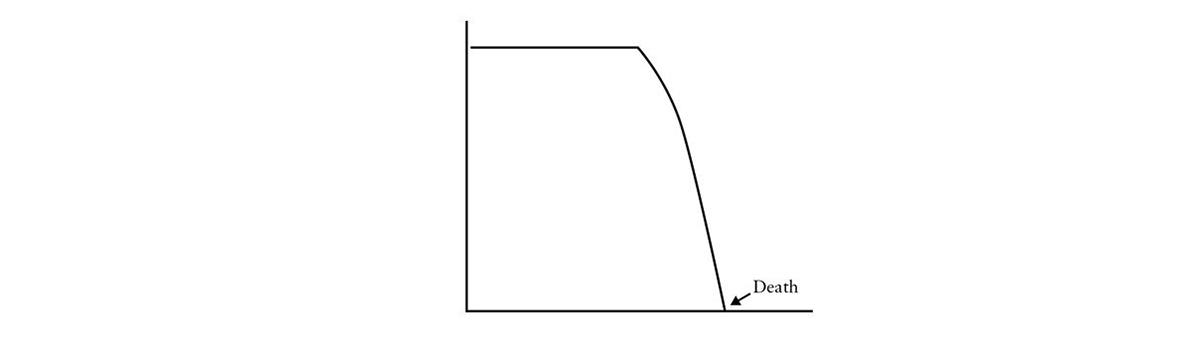

The first graph represents how things were before the advent of technological medicine:

In those days, Gawande says, “Life and health would putter along nicely, not a problem in the world. Then illness would hit and the bottom would drop out like a trap door.” (Henry Holt, Kindle edition, p25-26)

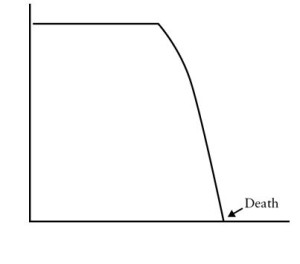

With the advent of modern therapies, things change, and life may proceed along the following pattern:

“[O]ur treatments can stretch the descent out until it ends up looking less like a cliff and more like a hilly road down the mountain.” (p. 27)

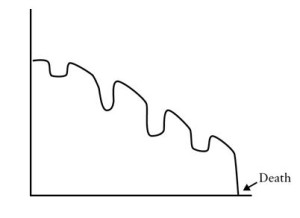

But then, Gawande adds that:

The trajectory that medical progress has made possible for many people, though, follows neither of these two patterns. Instead, increasingly large numbers of us get to live out a full life span and die of old age…[where] the culprit is just the accumulated crumbling of one’s bodily systems…The curve of life becomes a long, slow, fade” (p.27-28)

For the rest of the book, Gawande describes our struggles dealing with this “long, slow fade:”

medical science has rendered obsolete centuries of experience, tradition, and language about our mortality and created a new difficulty for mankind: how to die. (p. 158)

Now, at first glance, these life trajectories seem helpful in conveying the ideal we all desire and the course we want to avoid. Who wouldn’t wish a life that goes along a smooth horizontal path until “woosh,” we cut to the bottom in one fell swoop? Who would care to experience “the accumulated crumbling of one’s bodily systems” that Gawande so artfully describes? (His rendition is one of masterful realism. You can feel your teeth soften and your arteries crunch as you read).

But the peculiarity of the graphs, compelling as they may be, is that the y-axes have no label or unit. What quantity is this that we’d like to hang on to so dearly, and then give up all at once when our time is up? Gawande does not say.

The figures originally come from several articles (see, here and here) authored by gerontology scientists at the RAND corporation. In those papers, the y-axis is often labeled function. As we age, our functional abilities decline: our senses deteriorate, our bones and muscles weaken, our joints harden and, as a result, our ability to go on with life declines. At times, though, the papers also imply that the y-axis has to do with “well-being” or “symptoms.”

The graphs are similar to the illustration that depicts the concept of “Quality-Adjusted Life Years,” or QALY, used by health econometricians to make comparisons between the effect of different interventions. In the QALY graph, the y-axis contains two concepts at once: health and quality.

Now, one difficulty with all these figures is that well-being, function, quality of life, or health are not obviously quantitative measures that can be conveniently charted on a graph.

We may have “pain scales” and “functional assessment indices,” but these can only help measure a symptom or a performance in isolation. Symptoms and functional capacities cannot be combined to give a global sense of where one individual might fit on one of the charts above.

And what is health anyway, let alone “perfect health?”

A few years ago, Dr. Herbert Fred wrote an insightful editorial in which he noted that the phrase “to be in good health”

…applies only to the moment at hand, provides no guarantee, risks giving a false sense of security, and represents nothing more than an opinion, professional or otherwise

I wrote a letter in response in which I commented that:

In 1986, an editorial in CMAJ dealt with the question of defining disease and health.3 Contributors from diverse academic and private-practice backgrounds offered their perspectives, and others responded.4 There were as many definitions and viewpoints as there were essays.

What about quality of life?

Consider Stephen Hawking, who was first diagnosed with a progressive neuromuscular disorder at age 21, had to use crutches soon after that, and stopped lecturing a few years later. By the late 1970s his speech was hardly intelligible. He had a brush with death from pneumonia in the 1980s. He is now dependent on a ventilator and the use of facial muscles to activate his aid devices. Yet, despite these unimaginable difficulties, he has managed to produce some of the greatest accomplishments in theoretical physics of the last 50 years.

When Hawking dies and is asked by St. Peter to draw his life trajectory, how do you think he would sketch it? How would you sketch it?

Now, Gawande might object that these graphs are purely conceptual and need not convey a specific sense of mensuration for the variables in question. But if that’s the case, what is the point of using graphs? Clearly, according to him, there is something which, as life progresses, diminishes either gradually or abruptly. If something diminishes, it is a quantity. A quantity of what?

Besides, there are other parts of the book that lead me to believe that Gawande does take these graphs as literally pointing to a “quantity” of well-being, but before we get to those parts, we need to take…

A philosophical detour

Gawande, the RAND scientists, and QALY wonks are not the first ones to attempt to turn qualities into quantities. In fact, that conceptual alchemy is at the root of a philosophical paradigm elaborated two hundred years ago and which is still widely influential in our culture to this day.

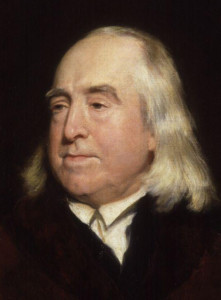

Jeremy Bentham was an early nineteenth century thinker whose philosophical contribution was to propose that passions, emotions, and feelings are quantitative entities which we combine into a “felicific calculus” by considering each feeling with respect to seven circumstances: intensity, duration, certainty, propinquity, fecundity, purity, and extent.

Man, Bentham believed, is driven to maximize his happiness and minimize his pain or suffering in accordance with this putative calculus.

As Murray Rothbard put it:

Bentham sought to reduce all human desires and values from the qualitative to the quantitative; all goals to be reduced to quantity, and all seemingly different values—e.g., pushpin and poetry—are to be reduced to mere differences in quantity and degree.¹

And by extending this personal utilitarianism to the community, Bentham famously proposed that “it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong,” a maxim about ethics now known as the principle of social utilitarianism.

Bentham’s idea would perhaps have ended as a quaint footnote in the history of thought were it not for the rise of social democracies and the advent of statistical science. When political systems emerged that would take it upon themselves to distribute “benefits” to the population, the felicific calculus was reincarnated into a much more respectable concept: the cost-benefit analysis.

The mathematical models that underlie modern cost-benefit analyses might be more “robust” or “sophisticated” than Bentham’s simple algebraic methods, but the principles are the same. Qualities have been turned into quantities and, in recent years, happyism has become a legitimate field of “scientific” research.² As Eric Posner and Cass Sunstein recently remarked, Benthaminism is alive and well.

The story of our life

To return to Gawande’s views on life and death, we should recall that Bentham was a disciple of David Hume, and lived at a time when philosophy was entirely captivated by Newton’s mechanics. In those days, intellectuals increasingly viewed the world as bodies in motion, colliding, acting, and reacting on one another, under the immutable laws of classical physics.

As a thoroughgoing empiricist, Bentham accepted Hume’s philosophical stance that reason is “slave to the passions” and that the self is nothing more than a bundle of experiences. And it is from that anthropological framework, from Hume’s conception of the mind as essentially subject to impressions, that Bentham proceeded to conceive of his felicific calculus.

Well, the concept of the self as a “bundle of experiences” is implicitly at the heart of Gawande’s book. Consider the following passage:

For human beings, life is meaningful because it is a story. A story has a sense of a whole, and its arc is determined by the significant moments, the ones where something happens. (p. 238)

Being Mortal is chiefly a collection of stories and is a commentary about the importance of stories, of how lives are formed by their experiences (e.g., p. 87), and how wisdom is “gained from long experience in life.” (p. 94). There is no mention at all in his book of any effect one’s reason might have on one’s outlook on life, independent of experience.

Instead, Gawande proposes that life is interpreted on account of the “experiencing self” and the “remembering self:”

When our time is limited and we are uncertain about how best to serve our priorities, we are forced to deal with the fact that both the experiencing self and the remembering self matter. We do not want to endure long pain and short pleasure. Yet certain pleasures can make enduring suffering worthwhile. The peaks are important, and so is the ending. (p. 239)

If I read him correctly, this distinction between the “experiencing self” and the “remembering self” only means that it is the totality of one’s life experiences that matters and that determines the richness and meaning of life.

Perhaps Gawande’s most explicit expression of his empiricist position is a passage later on where he states that :

No one ever really has control. Physics and biology and accident ultimately have their way in our lives. But the point is that we are not helpless either. Courage is the strength to recognize both realities. We have room to act, to shape our stories, though as time goes on it is within narrower and narrower confines. A few conclusions become clear when we understand this: that our most cruel failure in how we treat the sick and the aged is the failure to recognize that they have priorities beyond merely being safe and living longer; that the chance to shape one’s story is essential to sustaining meaning in life; (p. 243, italics mine)

One might wonder that if “physics and biology and accident ultimately have their way,” then who is the self who is not helpless, the “one” who’s shaping the story? Neither Hume nor Gawande give satisfactory answers to that question.

To return to the question of personal utilitarianism, Gawande seems at one point to precisely preempt such a charge:

Measurements of people’s minute-by-minute levels of pleasure and pain miss this fundamental aspect of human existence. A seemingly happy life may be empty. A seemingly difficult life may be devoted to a great cause. We have purposes larger than ourselves. (p. 238)

But how does Gawande explains these “purposes larger than ourselves?” By the fact that:

Unlike your experiencing self— which is absorbed in the moment— your remembering self is attempting to recognize not only the peaks of joy and valleys of misery but also how the story works out as a whole. (p. 238-9)

So measurement does matter, after all, since meaning results from the totality of peaks and valleys as our life story unfolds.

At any rate, the notion that life’s meaning derives from the stories we author—our “ego-dramas,” as Robert Barron would likely put it—is where Gawande is clearly at odds with Viktor Frankl. For Frankl advocated that meaning is transcendent. It resides outside of or beyond the human person, and is not simply the result of one’s cumulative life experiences.

One passage from Man in Search of Meaning makes that point clear:

I wish to stress that the true meaning of life is to be discovered in the world rather than within man or his own psyche, as though it were a closed system. I have termed this constitutive characteristic the “self-transcendence of human existence.” It denotes the fact that being human always points, as is directed, to something or someone, other than oneself–be it a meaning to fulfill or another human being to encounter. (Boston:Beacon Press, 2006, paperback edition, p.110)

Granted, Frankl also says that one of the ways that meaning can be discovered is

by creating a work or doing a deed or by experiencing something–such as goodness, truth and beauty–by experiencing nature and culture or, last but not least, by experiencing another human being in his very uniqueness–by loving him. (p. 111, italic mine)

But this experience of life leads to meaning and is not the meaning itself.

More important for this discussion, Frankl was clear that another way to find meaning is either through love or by suffering:

We must never forget that we may also find meaning in life when confronted with a hopeless situation, when facing a fate that cannot be changed. For what then matters is to bear witness to the uniquely human potential at its best, which is to transform a personal tragedy into triumph, to turn one’s predicament into a human achievement. (p.112)

Now, the differences between Frankl and Gawande are not vague abstractions for salon discussions, but have real life consequences. One example is the proper attitude toward suicide.

Frankl describes that in the Nazi camps, prisoners would commonly commit suicide, often by hurling themselves against electric fences. The justifictation seemed eminently reasonable: an outcome of death was near certain and would be an unspeakable horror if it took place in a gas chamber. And why give that satisfaction to the Nazis?

For Frankl, the response is not to grasp at straws of false hope that one could miraculously escape from the nightmare. Instead, one can find meaning and purpose in suffering, even in the godforsaken despair of a concentration camp. He relates one instance here:

For Gawande, on the other hand, since ultimate authority belongs to physics and biology, the suffering of aging or of a terminal illness is unnecessary and can ruin an entire life’s experience: “[I]n stories, endings matter.” (p. 239). Suicide is not only reasonable, but may be “assisted” and even be a “right.” (p. 243)

One final note:

Although he may not acknowledge it, Gawande is a notable figure in the current “less is more” movement in medicine. That movement seeks to counter the costly hubris of the technology and corporate-driven healthcare trend of the last fifty years.

If we accept the “trajectory of life” graphs as useful conceptual tools, then the old trend sought to push the line along the x-axis of time, come what may to the y-axis of quality. The new trend, on the other hand seeks to do the opposite: maximize quality on the y-axis, even if quantity of life, on the x-axis, is neglected or abridged.

Therefore, to the extent that both movements view human lives as graphs to be manipulated according to the whims of third parties, “less is more” is really more of the same: an objectification of the patient for the sake of one’s own interest or worldview.

Notes:

- Murray Rothbard (1995). An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought: Classical Economics. (Auburn, AL:Mises Press) 1995. p 58. Available free online.

- I am grateful to Mr. W. Bond for alerting me to this article by Deirdre McCloskey.

“No one ever really has control. Physics and biology and accident ultimately have their way in our lives. But the point is that we are not helpless either. Courage is the strength to recognize both realities. We have room to act, to shape our stories, though as time goes on it is within narrower and narrower confines. A few conclusions become clear when we understand this: that our most cruel failure in how we treat the sick and the aged is the failure to recognize that they have priorities beyond merely being safe and living longer; that the chance to shape one’s story is essential to sustaining meaning in life”

I think the author is saying that aging and accident are inevitable. But we have choices in face of these inevitabilities. I also think he’s saying that being safe and living longer loses meaning without the “chance to shape one’s story.” In other words if a person is merely confined to an aging facility – in effect a prisoner of the system – life loses its meaning, although one is still safe and alive.

It appears to me that the author is making an argument that one has choices under adverse conditions and that without choice, life loses its meaning.

Thank you for your comments, Joe.

I understand what you are saying, and I think you accurately paraphrase Atul Gawande’s words, but I still think there is an inherent contradiction or, at least, an ambiguity, when you (and Gawande) say that life loses meaning if you become confined to an aging facility or become “prisoner of the system.” If that’s the case, and if you equate meaning with control over your destiny, then you don’t really have any choice since accident and aging are inevitable. Frankl’s position is precisely to argue that you can find meaning even amidst the worst imaginable adversity and total lack of control, even within the horror of a concentration camp.

Michel

Very nice article Michel!

I’m wondering, though, why you stopped short of supplying YOUR take on what might contribute to meaning in life (or at least an appetizer)?

You clearly find fault with reducing meaning/quality to some measurable quantity; and you even hint at there being something more: “Frankl advocated that meaning is transcendent. It resides outside of or beyond the human person, and is not simply the result of one’s cumulative life experiences.”

But why not talk a bit more about that?

Given your references in other writings (e.g. including Lewis’ Mere Christianity), I suspect it (your view) may be informed by something we are not allowed to discuss too much in public as physicians…as doctors informed by evidence? Something transcendent? Perhaps even benevolent I dare say?

Re: suicide (and physician assisted suicide) – I wonder if Frankl’s stance could even be extended to the other end of the life spectrum…the ‘right’ to have abortion. But that’s opening up another can of worms.

Thanks again for the interesting article.

Jacob

Thank you, Jacob. If you read my blog carefully you will see that I’m not trying to hide anything. And if you have experience in writing essays, you know that it is best to stick to one message or convey one point across. Thanks for reading! Michel

I actually know very little about writing – and even less about writing essays – so your point is well taken.

My apologies if it sounded like I was implying you were trying to “hide anything”. My intent was to draw out more thoughts and discussion on what gives our patients (some suffering from ‘intolerable’ or ‘irremediable’ conditions) meaning in life because Gawande’s version is lacking to a certain degree. These sorts of discussions are important for physicians to have (loudly and in public) lest we lose our identity as a profession. Although some would argue that we are too late.

Next week, I will be talking to 10-14 year olds about what a physician does and about our role in society. I am afraid that it is becoming more difficult to describe being a doctor as healer steeped in a rich tradition (e.g. Hippocrates, Avicenna, Harvey, etc.) and easier to describe doctors like car technicians – some specialize in wheels, others in exhaust, but common to all is getting more miles out of the vehicle.

Further to your commentary in your other article “A deadly choice for the medical profession”, where you foreshadow physicians no longer understanding their role, perhaps one of the answers is to educate medical students about the history of medicine. An idea Sir William Osler had over 100 years ago, which still holds true in my opinion.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2401327/?page=1

Thanks again for your blogging! Feeling nice and alert, and even a bit more oriented.

Jacob

Thank you, Jacob. And yes, the metaphor of the car technician is the one most necessary to dispel.