Some say mammograms don’t save lives, and we order too many of them. That may be true, but which ones should we eliminate? The answer is not so easy after all.

Today’s post will deal with overdiagnosis, a concept preoccupying health care analysts, academics, and policy makers, and one whose importance is confirmed by the distinction of having its own dedicated Twitter hashtag.

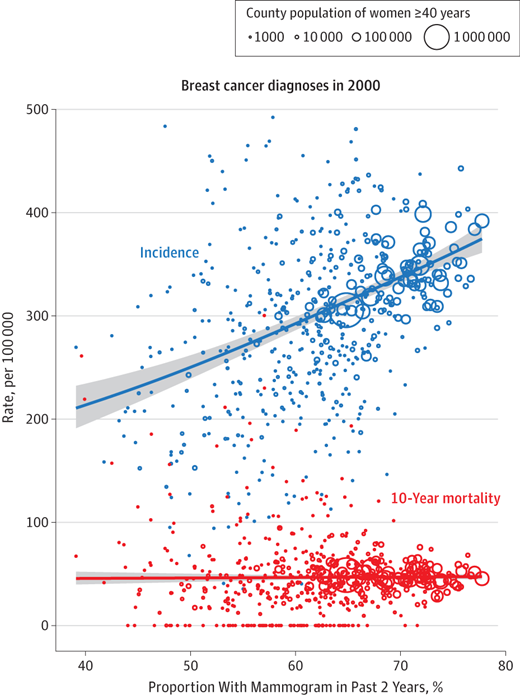

And if you follow the #overdiagnosis hashtag these days, you will surely encounter the following chart, excerpted from a recent JAMA Internal Medicine paper:

Each dot or circle on the chart represents a US county for which the proportion of mammograms performed, as well as the incidence (blue), and 10-year breast cancer mortality (red), are known. The lines “connecting the dots” show the relationship between these three variables.

Breast cancer incidence rises in counties where mammography is performed in higher proportion, yet mortality rates in such counties do not change compared to those counties where the screening test is performed less commonly.

How can that be? “Widespread overdiagnosis” is the answer.

In a recent online interview, Barry Kramer, Director of Cancer Prevention at the National Cancer Institute, clarifies that

Cancer overdiagnosis is the detection of asymptomatic cancers, often through screening efforts, which are either non-growing, or so slow-growing that they never would have caused medical problems for the patient in the patient’s lifespan.

They…represent an important cause of overtreatment, which can involve serious harms and toxicities such as deaths from surgery, major organ deformation or loss, and second cancers from radiation or chemotherapy.

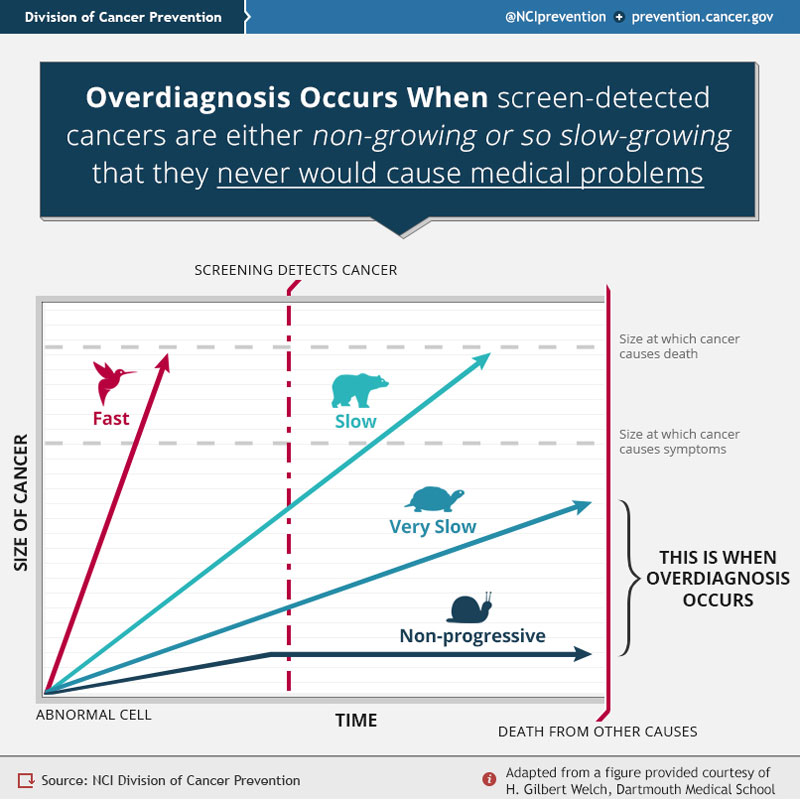

Overdiagnosis, then, is not a question of misdiagnosis or false positive tests. To illustrate the problem, Dr. Kramer offers the following chart:

Snail-type and turtle-type cancers, he explains, grow so slowly that their detection and treatment will not materially impact someone’s lifespan or symptoms. Bird-type cancers grow so fast that screening is also of no value. Bear-type cancers, on the other hands, grow just right, and are the ones best suited for screening. If one has such a cancer, the test can be detect it before symptoms occur and in time for treatment to produce benefit.

Prompted by the interviewer, Dr. Kramer emphasizes the implication of overdiagnosis: “People should know that not all cancers detected by screening need to be treated.”

But here’s the rub: overdiagnosis cannot be diagnosed.

Not even after the fact. At least, not in any given patient. The snail, turtle and bear cancers are concepts, not things. So far as we are able to read them properly, biopsies show “dysplasia,” not ursus or gastropod.

Each dot or circle in the mammography chart above does not represent a patient, but a collection of patients (in this case, counties). Concepts of incidence and mortality rates do not apply to individuals but to populations. Overdiagnosis is a hypothetical construct that can be assumed to have taken place only ex post facto, when the expected benefit for the group fails to materialize.

For any given person, whether overdiagnosis has occurred is anyone’s guess. As professor Sandra Tanenbaum recently remarked, the tools of clinical epidemiology that guide our medical decisions are “mostly silent on the inferential leap from aggregate to individual that is required for actual clinical care.”

How, then, are we to know which cancer should be treated and which should not, or which should be screened for and which should not? Faced with this uncertainty, it becomes apparent that the typical regimen of austerity nowadays recommended to cure overdiagnosis (“less is more“) cannot address the dual goal of decreasing costs and improving well-being, at least not with this particular condition.

Dr. Kramer, however, stops short of advocating for less screening, perhaps a wise move for a director at the NCI. Instead, he sets his hope on the development of “more accurate methods of predicting the behavior of screen-detected cancers at the molecular level.”

This is also the tack advocated by Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiang, CEO of NantHealth, a company determined “to capture big data in real time across the continuum for one single patient” and to bring cancer treatment “into the 21st century of molecular medicine.” A couple of days ago, Dr. Soon-Shiang told Modern Healthcare that “Unless organizations tie clinical care to the movement of new science, they will become dinosaurs.”

If health systems don’t tie care to new science they’ll “become dinosaurs.” http://t.co/HGOOGjs96T @solvehealthcare pic.twitter.com/74vXodoKxV

— MHgblesch (@MHgblesch) July 6, 2015

But is there a better name for a dinosaur than Big Data? In a recent JAMA editorial, Dr. Michael Joyner aptly observed that the promise of “sequencing more genomes, creating bigger biobanks, and linking biological information to health data in electronic medical records (EMRs)” may capture the imagination. However, “the promise of improved risk prediction, behavior change, lower costs, and gains in public health for common diseases seem unrealistic.”

Is the situation, then, hopeless? Are we destined to a perpetual culture of “Overkill,” to use Dr. Atul Gawande’s graphic rendition?

I’m not sure what the way forward is, but I find looking back to be usually instructive.

So perhaps, if we looked a few decades back, we might trace the etiology of cancer overdiagnosis to the launch of the War on Cancer in 1971. That martial call, issued by President Nixon, lent support to myriad “public awareness campaigns” vaunting the promises of precisely those screening efforts which Dr. Kramer identifies as mediators the overdiagnosis problem.

Perhaps, if we looked back a couple of decades more, we might discover that the pathophysiology of overdiagnosis could have come from a health care system designed to shield its beneficiaries from the financial consequences of medical choices. In such a system, patients embrace screening more readily and, undoubtedly, less critically than they would otherwise.

And perhaps if we looked back even further, we might find that a treatment for overdiagnosis could simply be to avoid the tendency, set in motion 100 years ago, but increasing in vigor ever since, to conflate public health and medical care.

Perhaps, then, a treatment for overdiagnosis, out-of-control costs, unnecessary harms, and dubious therapy might be to allow medical decisions to be made how they were meant to be made: between individual patients and individual healers setting together the terms and expectations of the arts and sciences of medicine.

UPDATE: A recent announcement was made at the meeting of the American Association of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM) that the radiation exposure from mammography is 30% less than previously estimated. Could the concern over #overdiagnosis be #overblown?