A couple of years ago, as I was trying to determine the best business model for my practice, I offered direct primary care (DPC) services to a few patients. Among them was WW, a then 57-year-old man who was well when I first saw him, but who ended up dying a year later in a very sad and dramatic way from a rare condition.

The extraordinary illness that struck W is worth describing simply on account of its rarity and its highly unusual manifestations. But in addition, it occurred to me that my experience with W may be of particular interest to the growing number of physicians and health care professionals intrigued by, or involved in, DPC as a practice model. This case exemplified the challenges and rewards of taking care of people with no insurance and with limited financial means.

I hope you will find this “clinico-pathological conference” to be of value. Although W’s ultimate outcome would likely have been the same under any circumstance, I’m sure his clinical course may have been tackled differently by another doctor. I welcome any feedback and discussion. This case offers much to think about, and I certainly wonder about some of the decisions that I made now that I reflect upon them.

The clinical information is in black type and some commentary about DPC challenges in blue.

W was a very kind and affable African-American man who first came to my office to establish a relationship in February 2013. He had no complaints but needed routine monitoring of his blood pressure and refills on his medications.

W lived about 50 miles away from my office, seemed to have modest means, and had no health insurance. Under his financial DPC arrangement, I received $45 per month and a $10 co-pay for each visit. I offered in office cardiac tests at a 50% discount.

W was first diagnosed with hypertension when he was in his 30’s. He did not recall undergoing any specific diagnostic evaluation at the time. He also did not follow through with any treatment recommendation. In the 1990’s, he obtained insurance coverage through a health maintenance organization. He began drug therapy for hypertension but was still not diligent with the prescribed regimen.

In 1998, he sustained a mild cerebral hemorrhage felt to be caused by hypertension. He recovered fully, but that event did not quite persuade him to become fully adherent to the prescribed treatment for his high blood pressure.

W lost insurance coverage during the great recession and, in 2011, began to see another direct primary care physician who skillfully persuaded him to take his medications regularly. He was well when he saw me in 2013.

His medication regimen at that point consisted of a lisinopril/HCTZ combination pill at 20/25mg daily, atenolol 25 mg daily, simvastatin 40mg daily, a nasal steroid spray as needed for perennial rhinitis.

His medical history was otherwise unremarkable. He had had childhood asthma but it had not bothered him since. On review of systems, he mentioned mild constipation and denied urinary symptoms. He had mild musculoskeletal neck pain.

W’s family history was incomplete. He had no information about his father. His mother died in her 70’s of sepsis in the aftermath of an operation. She had rheumatoid arthritis and possibly some peripheral vascular disease. A half-brother had died from chronic substance abuse, and two half sisters were apparently healthy.

He and his wife had been married for 19 years. He had 5 adult children. He worked in the information technology department of a company and was also the pastor of a small congregation. When he was younger, he was an avid and proficient basketball player. Lately, he had become generally sedentary but would still go to the gym routinely for light exercises. He never smoked and never drank alcohol.

His height was 6’4″ for a weight of 275 pounds. He had a resting bradycardia with a pulse rate in the high 40’s and occasional extrasystoles. His blood pressure was 120/80 in both arms. I remember joking that he had better blood pressure control than his wife. (She also became a new patient of mine that day, but had a history of only “borderline” hypertension). The rest of W’s examination was unremarkable.

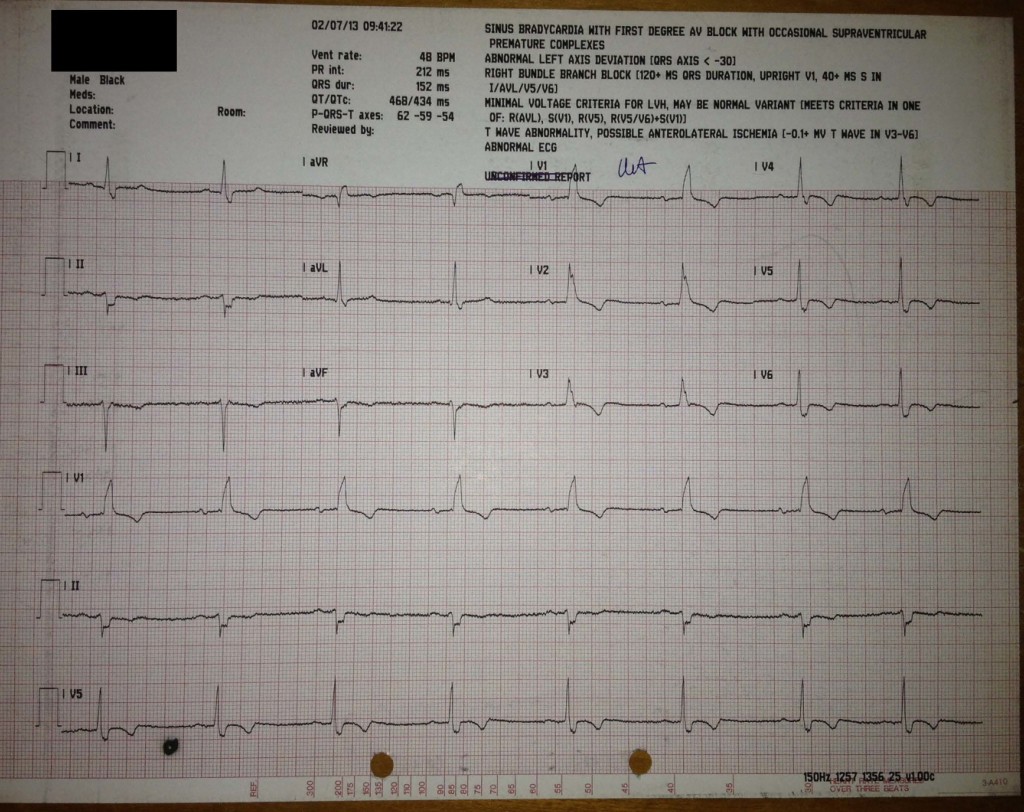

Although the DPC setting calls for being parsimonious with testing, I felt that a baseline ECG would be helpful. I suspected I might find signs of left ventricular hypertrophy, but not much else. The sinus bradycardia also encouraged me to order the test.

An ECG showed sinus bradycardia at 48 bpm, first degree AV block (PR = 212 msec), left anterior hemiblock, complete right bundle branch block, as well as significant anterolateral T wave inversions:

This is not what I expected to find, but in an asymptomatic man, I wasn’t sure what to make of it. Perhaps he had a familial premature conduction system disease. I felt he was at risk for needing a pacemaker in the future. I also thought an echocardiogram was in order, especially to exclude an asymptomatic cardiomyopathy. I became a little bit nervous about him.

Routine blood tests are shown here. I took note of, but did not address, the mild elevation in the serum calcium level. The tests were otherwise unremarkable.

I asked him to gradually discontinue his atenolol while monitoring his blood pressure over a course of a few weeks. We corresponded by phone and email about home BP measurements. During that time, W relayed one episode of dyspnea on exertion lasting 5 minutes. Once atenolol was discontinued, his blood pressure remained stable on his moderate dose of lisinopril-HCTZ and his resting pulse increased to the low 60’s.

In June 2013, W returned to my office for a repeat ECG (off atenolol) and an echocardiogram. On that day, his blood pressure was ~130/80 and we confirmed that his home blood pressure device gave adequate readings.

He also reported feeling better off the atenolol. In retrospect, he thought that he had had mild exertional chest tightness chronically for a few years, a symptom which was now improved after the atenolol was discontinued.

The ECG showed sinus bradycardia at 55 bpm, as well as persistent tri-fascicular block and anterior T wave abnormalities. The first degree AV block did not improve (PR interval 210 msec).

The echocardiogram study showed:

- Normal left ventricular cavity size and systolic function without wall motion abnormalities

- Mild concentric left ventricular hypertrophy

- Mild impairment in diastolic function (Grade I)

- Normal left atrial volume index

- Normal cardiac valves, but “the anterolateral papillary muscle [was] very prominent and the posterior one diminutive or even absent.”

- No valvular incompetence, including in the tricuspid valve

- No aortic or pericardial abnormalities

I did not give further thoughts to his ECG abnormalities at that point. He was asymptomatic, I informed him of the findings, and educated him about symptoms of progressive conduction system disease to watch out for (lightheadedness, syncope).

He was well for the next 6 months. In December 2013, however, he contacted me to relate an episode of “near collapse” that had occurred ten days before. He had been rushing around his church and, after walking very fast, felt his legs getting weak and nearly lost consciousness. He also felt very short of breath during that episode for a few minutes.

He also reported that his blood pressure had been running lower than normal and was now commonly ~ 115 systolic at rest. According to him, his pulse rate at rest remained OK.

After probing him more about his exercise symptoms, he stated that for several years he had felt short of breath walking up an incline, but was fine as long as he was able to rest. His normal gym routine consisted of mild “jumping jacks” and light weightlifting, but these activities were also done with frequent rests. Lately, though, he had felt much more dyspneic than usual and therefore had not gone to the gym in several weeks.

Apart from that episode 10 days before, he felt generally fine and had no constitutional symptoms.

The constellation of signs and symptoms was very concerning. I considered sending him to the emergency department but he was already 10 days past his event and I was concerned he might be discharged without a diagnosis and be saddled with a very high bill. He was precisely in the income category of people who are liable to be completely ruined by medical bills.

I was concerned about coronary disease or some electrophysiologic disorder, given the extensive conduction abnormalities at baseline. Either of these would be difficult to manage as an outpatient, but I thought I might be able to get more clarity with non-invasive testing first. Expensive tests would have to be ordered through a dropper. I was getting more nervous.

I asked him to come the next day for a plain exercise treadmill test. I knew it could be of limited diagnostic value for coronary disease, given his baseline abnormalities, but I wanted to at least objectively see if his baseline ECG had evolved, check his exercise capacity, and see if he had any evidence of chronotropic incompetence (an inability to increase his heart rate with exercise due to conduction system disease).

His physical examination was unremarkable except that his resting blood pressure was an unusual 110/70. He did not look anemic and his lung examination was normal.

His baseline ECG was unchanged, except that now he had frequent premature atrial complexes at rest.

We proceeded with the “modified” standard Bruce protocol, which means that the treadmill exercise started very slowly at 1.7 mph at 0% grade. His exercise tolerance was very poor. He lasted 7 minutes and 30 seconds on the treadmill (middle of standard stage I) and the test was stopped because of shortness of breath. His heart rate rose rapidly to a peak of 120 bpm (75% of maximal age-predicted heart rate) from a baseline of 64. His blood pressure also rose to 150/70. There were no ischemic changes.

At this point I was quite puzzled. He did not have chronotropic incompetence or exercise-induced heart block to explain his marked shortness of breath on the treadmill. I was somewhat reassured that his blood pressure rose with exercise and that there were no major ischemic changes on the ECG, making coronary artery disease a less likely cause of his symptoms, although I felt that I could not exclude CAD on the basis of that test. He might also have lung disease, but his examination was unremarkable in that respect.

I was quite at a loss to explain what was going on, but I primarily wanted to identify or exclude the most lethal and most correctable possibility which, in my mind, remained coronary disease.

I advised him to avoid any exertion and felt I needed some time to think through the next course of action.

He came for a follow-up a couple of months later in February 2014. He was still experiencing occasional episodes of dyspnea on exertion, but none as severe as the one in late November. His weight was now 242 pounds, a loss of 30 pounds compared to when I first met him a year before. I don’t think I appreciated the extent of the weight loss, and he did not specifically mention any concern about his weight that day.

His blood pressure was a remarkable 114/70, for someone who, a few years earlier, had had a hypertensive cerebral hemorrhage.

I spoke with him and we agreed to try to proceed with a CT coronary angiogram which, at a tag price of $1250, was an expense he could afford, although not without significant hardship. I ordered some repeat blood tests.

The blood test results came back in mid February 2014 and are shown here. He was not anemic and his renal and liver function were normal. Mild elevation of the serum calcium remained. Remarkably, his LDL level had jumped to nearly 200 mg/dL from a value of 136 a year before, despite his continued use of simvastatin. As we were finalizing the arrangements for the CT angiogram, I asked him to switch to atorvastatin 80 mg.

There was some delay in getting the CT angiogram arranged, but a date was set for March 15. On March 10, W emailed me that his blood pressure was now consistently less than 90 systolic. He stopped his blood pressure medications and felt somewhat better, but the BP was still low, now 90-100. He had some orthostatic lightheadedness.

This low blood pressure and lightheadedness had caused him to miss work for 2 days, but he had returned to his job. He was obviously not feeling very well. His only medication at this point was atorvastatin 80mg daily.

I asked him to get an immediate morning cortisol level and additional blood tests, and to come to my office as soon as possible. I cancelled the CT angiogram.

In my office, he expressed concerns about his weight loss and reported a marked loss of appetite with early satiety over the previous few weeks, but no other gastrointestinal symptoms or evidence of bleeding or volume loss. The blood pressure was 104/70 lying down and 80/60 standing. His pulse rate was in the 60’s or 70’s, without much change with posture. The physical examination was unremarkable. He did not appear dehydrated. The ECG was unchanged. A limited echocardiogram showed his LV systolic function to be normal. I was growing increasingly concerned, and began to wonder about a gastrointestinal process.

The blood test results are shown here and were followed in short order by another set of blood tests shown here.

Then a light bulb went off in my head.