Soon after publishing our second podcast episode on brain death, this article from Newsweek came into my Twitter feed: “Endorestiform Nucleus: Scientist Just Discovered a New Part of the Human Brain.”

According to the article, an Australian researcher may have discovered an island of neurons heretofore undescribed and which may be involved in important motor activities.

The same article also mentions the “discovery” early this year of a new organ to be called the interstitium. As in the case of the endorestiform nucleus, the claim for the interstitium is not that scientists have discovered a new material part of the body so far unknown, but that a known part of the body that previously did not attract the attention of physiologists is now found to have a function that is capturing their attention.

These “discoveries” illustrate nicely a philosophical point about body parts.

We tend to think of body parts in the same way we think about parts of a machine. For example, we can all point to an arm, an eye, or a stomach in a human body in the same way that we point to a steering wheel, a radiator, or a seat in a car. Each part of the human body has a function and likewise each part of the car has a function.

But there’s something distinct about parts of living organisms compared to parts of machines.

The boundary between where a part starts and ends is clear cut in a machine. In a machine, the parts typically exist first before being assembled. The separation between one part and another part will typically be a corner, or a joint, or a welding of some sort, and we could presumably extract the original part with great precision—at least mentally, if not physically.

This is not the case with bodies of living organisms which develop from within, so-to-speak. A hand is a bunch of cells and tissues that have differentiated during embryonic development into the part that we usually identify as being “distal to the wrist,” but the separation between the wrist and the hand is not straightforward.

Sure, we can say that the metacarpal bones and the phalanxes all belong to the hand, while the wrist bones all belong to the wrist. But what about the blood vessels, nerves, and skin? Where do we draw the line as to where the skin is “hand skin” versus “wrist skin”? Or should we even include the skin as part of the hand? If so, why? If not, why not?

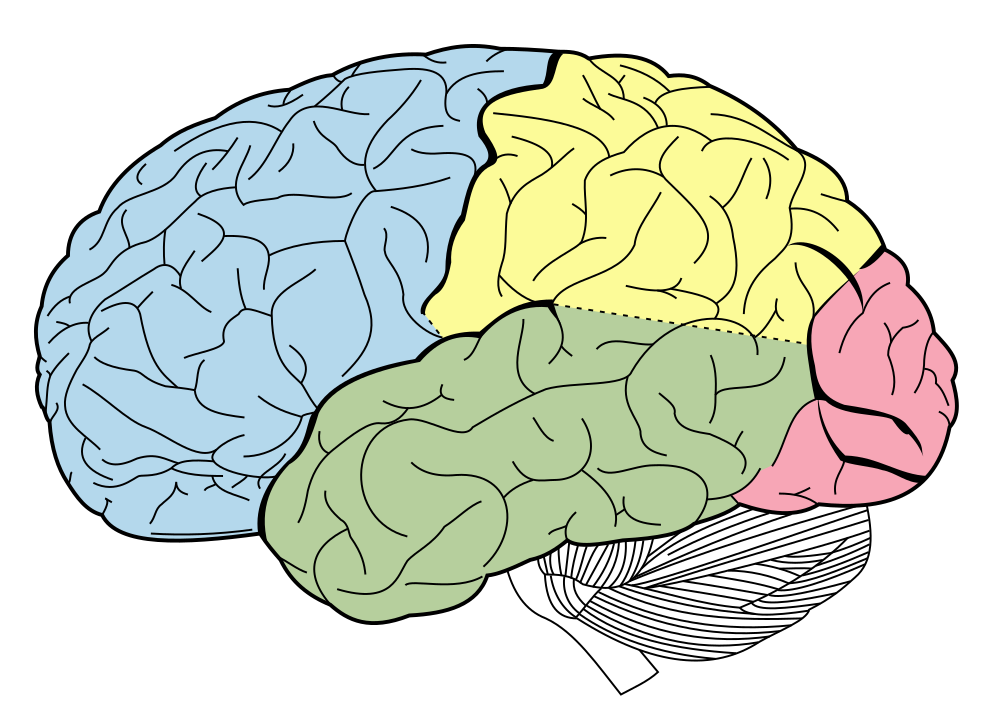

In a way, a hand, a wrist, a stomach, and even a brain are strange beings. They are partly real things out there in the world and partly ideas or conventions in our minds. They don’t have the same real distinctness as the parts of a machine have. That’s unlike the whole body, which is one total body out there in reality, whether another person is observing it or not.

These reflections allow me to poke yet another hole in the argument that brain death = death of the human being.

Related Podcast Episodes:

[Ep. 45 Brain Death at the Bedside]

[Ep. 35 Why Brain Dead Isn’t Dead: An Introduction to “Shewmon’s Challenge.”]