To conclude this 3-part series, I will discuss the relationship between shared decision-making (SDM) and evidence-based medicine (EBM), as the two are intimately connected.

As I indicated in part 1, SDM did not attract the attention of academics until the late 1990s. It is only then that publications on SDM began to appear routinely in the medical literature, and their numbers have exploded since the early 2010s (see chart). Yet shared decision-making was proposed by the Presidential Commission’s ethicists as far back as 1982. What accounts for the delay in interest?

The simple answer is that the development of SDM had to wait for the appearance of the evidence-based medicine movement on the healthcare scene in the early 1990s. And it makes perfect sense that SDM would require EBM to flourish, since EBM was proposed precisely as a scientific and objective antidote to “eminence-based medicine,” which is one expression of the culture of medical paternalism that SDM was supposed to be countering.

The scientific patient

Prior to EBM’s systematic elevation of clinical research above other forms of evidence, a physician recommendation was naturally understood as representing his or her best clinical judgment. And given the inherent “asymmetry of information” in the doctor-patient relationship, it’s hard to imagine how, sans EBM, a shared decision could have been achieved.

With the rise of EBM, however, everything changes. Now physicians can share data with their patients as the means to engage in the “process of accommodation” that the ethicists felt should form the basis of SDM. In the same way that data allegedly clarifies for physicians the best path forward, so would data presumably serve the process of SDM by letting patients see for themselves the rationale behind each treatment decision.

Before EBM, Marcus Welby would tell Linda that she ought to take rosuvastatin. That was that.

With EBM, Marcus Welby can tell Linda that—based on her established risk profile—rosuvastatin can reduce the probability of a cardiovascular event by 1.2% at one year…by 9.6% at 5 years…and by 17.8% at 10 years. He might also tell her that the expected risk reduction with rosuvastatin, relative to what it would be were she to take a daily placebo pill instead, is (roughly) 27.4%.

Welby can also tell Linda that the “number needed to treat” before a patient is expected to incur benefit from rosuvastatin is X, while the number needed to treat before a patient is expected to incur harm from rosuvastatin is Y.

He might further tell Linda what the guidelines documents, published by EBM experts, state regarding the treatment of a patient like Linda. And, if he is particularly thorough, he might even point out with amusement the nuanced differences between American guidelines, Canadian guidelines, and European guidelines. Those differences could be stemming from different choices of statistical analysis of the data, from different emphases about risk trade-offs (based on cultural, social, or economics differences between these regions), or even from the potential but scientifically documented influence that the pharmaceutical industry can have on guideline writers who accept gifts or honoraria in the course of conducted their research and professional activities.

Armed with this scientific information, Linda is no longer subject to the opinion of the doctor, but she can decide for herself (and, apparently, decide “simultaneously” with her doctor) whether to take the pill or to pass. Free at last from the grip of paternalism!

Decision-aids

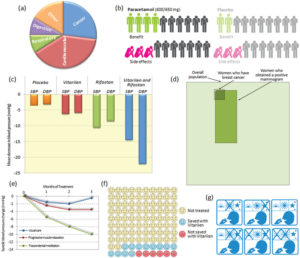

But that is not all. Shared decision-making’s appeal to EBM has spurred an entire industry of “apps” and other tools—decision-aids—to help convey the data to the patient in a more digestible manner. These devices require the input of the relevant physiological variables (e.g., for statin therapy decision-aids, age, blood pressure, cholesterol levels, smoking habits, etc., are inputted in the calculator). The output is a visual depiction of risk, usually portrayed as patterns of smiley faces 🙂 and frowny faces 🙁

Some of these are simple and pleasing to the eye, like this one developed by the Mayo Clinic:

Others are more ambitious, and therefore more complex, especially if they are meant not only to aid a decision, but also to promote a certain level of “health literacy” necessary for SDM, like this one:

Unfortunately, no matter how ambitious or simple these decision-aids may be, they do not yet aid the patient in understanding that statistics can hardly predict what matters, meaning what will happen to them individually. If Linda were to ask “which smiley or frowny face am I on this chart?” she may find shared decision-making to be more perplexing than the simple typing of a few physiological parameters on a risk calculator would suggest.

EBM <3 SDM

If the rise of EBM was the impetus for the swell of interest in SDM, likewise SDM offered a much-needed complement for EBM.

When EBM was first introduced in the early 1990s, early critics of the movement pointed out that the establishment of an explicit hierarchy of evidence, with the randomized controlled trial at its apex, would easily threaten individualization of care.

To defend themselves against the charge of promoting “cookbook medicine,” EBM leaders added an important corrective to their definition of this ideal practice. This correction has been graphically rendered in what is probably the most iconic image in the entire medical literature:

By one of the most enduring act of scientific wishful thinking in modern times, David Sackett and his followers have carefully embedded EBM at the intersection of 3 pillars of excellent practice: clinical research evidence, clinical judgement, and patients’ values and preferences.

But how should patient preferences be determined? Sackett did not elaborate on this when he wrote his most cited editorial, but within the next few years, proponents of EBM would obviously find in SDM a missing piece of their puzzle.

And the rest is history. Read the latest paean to the virtues of EBM and you will find SDM extolled as well. Conversely, search the entries for SDM at the Mayo Clinic website, on HealthIT.gov, in the pamphlets of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, or in the pages of JAMA and NEJM, and you will find that SDM invariably means bringing EBM to the patient.

EBM loves SDM, and the feeling is mutual.

It seems to have turned out that the EBM/SDM model ends up as a tempting default for the physician afraid to exercise his/her judgment, hedging for treating the patient as purely a statistic (consciously or unconsciously attempting to protect him/her self from liability, and secondarily to “do no harm”, knowing that most of the time there will be no adverse effects), nevertheless, without ultimately focusing on the individual patient, a great deal is lost. And nothing, no strategy, can spare the physician from responsibility once he/she signs or doesn’t sign the Rx. Focusing on the individual requires an astute interest in the person/patient, acknowledging that there are irreducible uncertainties no matter what decisions are made.

Amen!

“If Linda were to ask “which smiley or frowny face am I on this chart?” she may find shared decision-making to be more perplexing…”

You are hinting again at your “patients as mental incompetents” worldview. Is this question less perplexing to you than to Linda? If you don’t know which group she will fall into, don’t sneer at her for not knowing! Why can’t you admit your shared uncertainty and ask her which risks she is more comfortable with? At least those smiley-face charts will prevent the doctor from saying to Linda “If you don’t take this drug you’ll have a heart attaaaack!” [when she may have a 1% per annum risk].