[This is part 2 of my paper presentation at AERC 2016 at the Mises Institute. Find part 1 here and the audio here.]

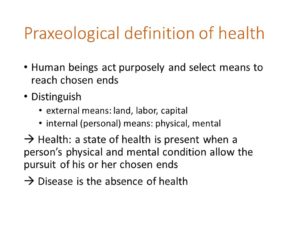

I would therefore like to entertain an interpretation of health rooted in the view that human beings are persons acting purposely, persons who select means to achieve chosen ends, which is the framework of praxeology.

I would therefore like to entertain an interpretation of health rooted in the view that human beings are persons acting purposely, persons who select means to achieve chosen ends, which is the framework of praxeology.

Under a praxeological framework, I would distinguish external means such as land, labor, and capital, which are generally the concern of economic theory, from internal means, such as the physical and mental conditions of the person that allow him or her to pursue chosen ends.

Health, then, may be defined as the state that is present when a person’s physical and mental conditions allow the pursuit of his or her chosen ends. Disease, then, is the absence of health.

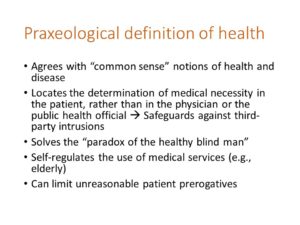

Of course, the first thing to do here is to ensure is that the definition of health corresponds to our common sense understanding of the term, and is not simply an intellectual abstraction. This is work that needs to be done carefully but, today, I simply wish to remark that conditions which we commonly conceive of as diseases, for example, heart attacks, trauma, pneumonia, cancer, and even the common cold, generally do interfere with a person’s pursuit of chosen ends, and therefore seem to cohere with our definition of health and disease.

Of course, the first thing to do here is to ensure is that the definition of health corresponds to our common sense understanding of the term, and is not simply an intellectual abstraction. This is work that needs to be done carefully but, today, I simply wish to remark that conditions which we commonly conceive of as diseases, for example, heart attacks, trauma, pneumonia, cancer, and even the common cold, generally do interfere with a person’s pursuit of chosen ends, and therefore seem to cohere with our definition of health and disease.

An important consequence of this praxeological interpretation of health is that it locates the determination of medical necessity within the patient, rather than in the physician or public health official, since only the patient knows what his or her chosen ends are. The definition can therefore safeguard against unwanted third-party intrusions in healthcare.

Moreover, our interpretation may actually solve what I call the paradox of the healthy blind man. Under the machine concept of health and disease, a blind person could never claim to be healthy, since a part of the body is obviously and objectively defective. Yet, undoubtedly, many blind persons and many other persons with serious disabilities actually consider themselves to be perfectly well and healthy, if asked about health in the context of a routine conversation. I believe that they do so because, despite their disabilities and infirmities, they are able to pursue their own chosen ends without undue difficulty.

In fact, a praxeological conception of health would promote self-regulation in the use of medical services. Rational beings naturally adjust their chosen ends according to the means that are realistically available to them, and that includes the internal means, namely one’s physical and mental conditions. Therefore a person’s sense of health may be maintained despite the presence of some objective dysfunction. This may be particularly pertinent in the case of the elderly, who may naturally curtail their chosen ends as they age, and claims for medical services would not necessarily rise in proportion to physical decline.

Now, one objection to my definition is that it may encourage unreasonable or irrational subjective determinations of health and disease. Imagine that I choose, as one of my ends, to become a linebacker for the Dallas Cowboys. Should my inability to gain enough muscle mass be considered a disease? According to my definition, it could, but I will address this difficulty in the next slide.

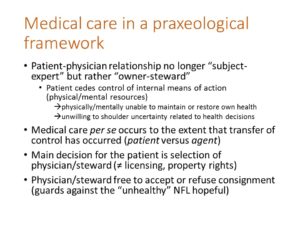

Let’s first note that the nature of the patient-physician relationship changes in the praxeological framework.

Let’s first note that the nature of the patient-physician relationship changes in the praxeological framework.

In this framework, we are no longer dealing with a subject-expert relationship, but with what I would call an owner-steward relationship. The patient is the rightful owner of his body but, in the course of medical care, he or she delegates control of the body to the physician. The physician is entrusted to work on the body, with the understanding that the goal is to help the patient achieve a condition where he or she can pursue his or her chosen ends, to whatever degree possible.

The transfer of control is particularly evident and complete in the case of surgery, but it also occurs in lesser degrees even in more routine medical care, when a patient agrees to ingest a medication, or to submit to the advice of the physician, since that medication or that advice invariably aim at changing the patient’s internal means of action, namely his or her physical and mental conditions.

Patients may choose to cede control of their bodies for a variety of reasons. They may be unable to maintain or restore their health on their own, or they may be unwilling to shoulder the uncertainty related to health decisions. There may be other reasons as well.

I would propose that medical care per se occurs only after control over the body has been transferred by the patient to the physician, and the patient submits, either implicitly or explicitly, to the actions of the doctor. In fact, this distinction would recover the original etymology of the word patient, which is opposed to agent.

And the main decision confronting the would-be patient is in the selection of the physician/steward. In that regard, licensing laws could be viewed as impinging on property rights, the rights to legitimately transfer care of one’s property—one’s body—to another person.

Of course, the physician/steward is not obligated to treat the person, but is free to accept or refuse the consignment of the body. That prerogative of the physician will, to some degree, safeguard against the problem of unreasonable or irrational health concerns on the part of individuals. In fact, this is an advantage over the empiricist models of health, since those models cannot easily deal with irrationality and unreasonable demands.

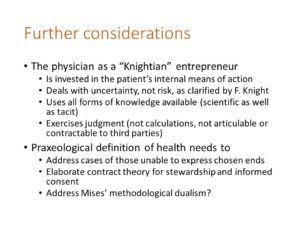

In this last slide, I would like to discuss additional concepts borrowed from economic theory.

In this last slide, I would like to discuss additional concepts borrowed from economic theory.

One concept is that a physician trained in the Austrian school of medicine would conceive of her role as a Knightian entrepreneur. She would see herself as being invested in the patient’s internal means of action, bearing in mind the patient’s chosen ends.

The Austrian physician would understand that she is dealing with uncertainty, and not risk, as clarified by Frank Knight. Risk has to do with repeatable events and outcomes that can be quantified. In medicine, we are dealing with unrepeatable human affairs and unquantifiable uncertainty.

To make medical decisions, she would use all forms of knowledge available to her including tacit, as well as scientific and technological knowledge.

And she would view her medical decision the way entrepreneurs view entrepreneurial decisions, as exercising judgment. This is in distinction to the way medical decisions are currently considered under the machine model, namely, as calculations.

As Knight proposed, entrepreneurial judgment is not articulable, and therefore not contractable to third parties. The Austrian physician will not contract with a third-party to provide care as if it were an objective, measurable entity.

Finally, additional considerations that the Austrian theory of medicine must address include the cases of those unable to express chosen ends, the need to elaborate a contract theory for stewardship and informed consent, and probably the need to address Mises’ methodological dualism, since the connection between the physical sciences and medical care is close, and a sharp methodological separation may be counterproductive in the long term.

Kudos on an impressive, well articulated ambitious project.I look forward for more to come.

Thank you, James