Joe Rogan is notoriously difficulty to pigeonhole. He is pro-gun rights, anti-cancel culture, and voted for Libertarian candidates in 2012 and 2016, but he also holds progressive positions on many issues, supported Bernie Sanders in 2020, and is not necessarily opposed to big government programs.

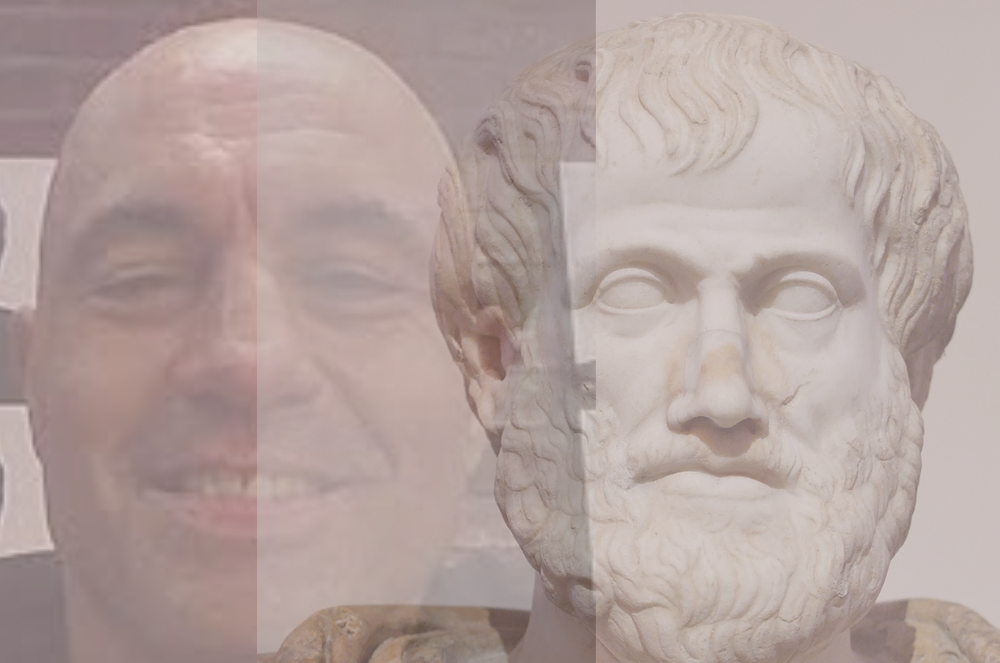

I suspect that much of his appeal indeed comes from seeming “pragmatic” rather than ideological. But after listening to him on a recent excellent episode with guest Michael Shellenberger, it occurred to me that Rogan’s leanings may also be those of a philosophical realist

I’ve said and I repeat it…it’s a mantra, it’s part of my philosophy: You can’t be married to ideas. Ideas are just a thing that you examine. If you get married to an idea and you support it even though, like…like a corrupt district attorney would do…like you thought a guy was guilty and even though you had evidence that would exonerate him you keep prosecuting him…We all have ideas that we bounce around that are incorrect, and the only way you find out about that is if you’re confronted with better evidence…

(It seems fair to assume that he uses the word “evidence” here as a stand-in for reality, i.e., for things that are independent of how we think or feel about them.)

An attention to reality is also evident when Rogan discusses abortion, as he does occasionally on his podcast. When he deals with that topic, he hones in on the fact that the humanity of the fetus is a key determinant of the issue. His reason for being pro-choice is that he thinks that the anti-abortion position is based on the “idea” that a blastocyst is a human being, rather than the real fact that it is.

Rogan knows that a well-formed baby in the days or weeks before it is delivered is clearly human, but he has a hard time ascribing humanity to the blastocyst. It is because he imagines the change from “life form” to “human being” to be a fuzzy transition that he consider abortion “a complicated weird thing.” If he could come to realize that the blastocyst is really a human being, i.e., human in reality and not just in the mind of some religious people, then the question of abortion would presumably be much simpler. It’s very instructive to watch him struggle with that topic in this clip.

At one point in the conversation with Shellenberger, Rogan sings the praise of Russell Brand for being a progressive who has also successfully broken through the ideological silos. Shellenberger reacts by speculating that because Brand is a recovered addict who has had to confront his own mortality, he has developed a “spiritual orientation, or at least an orientation to our common humanity” which enables him to avoid a toxic commitment to ideology and to enter into healthy conversations with people with whom he may disagree, such as Candace Owens. Rogan emphatically concurs: “Shared humanity is so crucial to all this!”

Well that, too, is an intuitive nod to realism: explaining how something like humanity can be really shared among individuals is one of the things philosophical realism does best. Joe Rogan should take note.

————

As a philosophical principle, realism has two prongs. The first is the acknowledgement there is a “reality out there” whose existence and behavior is independent of whether or how we think about it. That’s usually not controversial and few people are so radically anti-realist as to deny or seriously doubt the existence of an extra-mental reality. (I advise staying clear of those individuals.)

The second prong is the more controversial one that the human mind can actually know the things in reality as they are through the use of our senses and the use of reason.

Now it’s important to avoid a common caricature: Philosophical realism doesn’t hold that we can grasp or intuit any real thing we encounter immediately, nor that we can understand reality in its entirety by reasoning about what our senses tell us. Our capacity to know things clearly has some limits.

But what realism does hold is that we can ultimately gain knowledge of things “as they are.” We neither construct reality with our mind, nor is reality opaque to us, knowable only through some mental filtering mechanism, as Immanuel Kant’s softer anti-realism would have it.

In a way, philosophical realism is a defense of common sense (if it looks like a duck…) but that defense of common sense is itself difficult to defend and even more difficult to explain. It took the monumental genius of Aristotle to rigorously justify realism against its detractors through the development of a “metaphysics” which avoided the errors of Plato’s hyper-realism. It took the subsequent contributions of other geniuses like Thomas Aquinas, John Poinsot, and Charles Sanders Peirce to further build up the realist edifice.

Those metaphysical principles are far from intuitive. It’s not at all trivial to grasp the concepts with which to demonstrate why a blastocyst, a Black slave, a brain dead body, and a university professor are all equally human.

Despite its accomplishments, philosophical realism has never taken hold for long in human societies. Aristotle was not influential among the Greeks and even less so among the Romans. Arab philosophers relished his thought, but realism had little impact on Islamic societies. Even in the medieval West, Aristotelian metaphysics flourished in the universities for only a couple of hundred years, if even that. By the late 13th century it was undermined by “nominalist” philosophers mistakenly motivated by theological objections (they assumed that the realistic account of species undermined the omnipotence of God). By the the end of the Renaissance realism was openly spurned, if not scorned.

The beginning of modernity, in fact, is largely identifiable by a widespread rejection of realistic principles, and that rejection is evident in how we are nowadays trained to interpret our sense experience of the world. To give some easy examples:

- The water in the glass may seem clear and simple, but water (and everything else) is in fact a mixture of atomic and subatomic particles swirling in the void. The rose out there may look red, but the redness is our subjective experience of colorless electromagnetic light waves. In reality, there is neither simplicity nor clarity nor color “out there.”

- We may imagine that biological species are neat categories, but biological evolution happens at the level of the individual. Species are nothing more than a mental grouping of “similar” individuals seen from the distance of thousands or millions of years.

Our senses, then, do not truly give us access to reality as it is. At best, we can “model” reality, subject it to more-or-less violent interventions, and see if it behaves according to our model. If the model predicts how the intervention turns out, and if those predictions help us invent steam engines, build automobiles, create iPhones, and alter immune responses to ward-off viruses, then we obtain many material comforts. Understanding the world on its own terms, however, can only remain a matter of idle speculation.

The anti-realism of science (or, more properly-speaking, of scientism—the reduction of all valid knowledge to scientific knowledge) is the main reason we end up debating the humanity of the embryo. Science per se has no means of distinguishing universals and answering the question of whether this particular life form embedded in that particular womb belongs to that species. Science usually takes universals for granted from our intuitions, but when our intuitions fail us because of our philosophical confusion then science shrugs.

To be clear, scientific discoveries are not the reason realism was rejected at the end of the Middle Ages. Historically, it was the other way around. Philosophers rejected realism first and, in the process, created the conceptual tools that made the scientific revolution possible. Francis Bacon knew nothing about the atom. He just had a theological hunch that Nature was holding secrets that needed to be “revealed” through experimentation.

Scientific achievements are also not the reason that realism has generally been unpopular throughout history: Claiming that we can’t know reality as it truly is gives more weight and more license to our personal, philosophical, or societal preferences. But mistaking our desires for reality is costly in the long run (pace John Maynard Keynes). Without realism, things quickly devolve into relativism and subjectivism, as a survey of current hot button issues should make abundantly clear.

————

Brian Kemple is a very bright and articulate philosopher who is committed to turning the anti-realist tide and to countering the mostly navel-gazing, nonsensical morass that contemporary philosophy has become. It’s a tall order, but he’s off to a good start.

Kemple is a fully-credentialed philosopher who completed his doctoral dissertation under the late John Deely. He has a number of publications under his belt, as well as a couple of book chapters and a short self-published book that is an Introduction to Philosophical Principles.

A little over 2 years ago, he established the Lyceum Institute, a digital platform that supports a community of learners of all levels who wish to inquire about real philosophy and develop an intellectual discipline for it. He has also launched Reality Journal, a scholarly publication which offers top notch essays and articles, including this introduction to philosophical realism. But if you’d rather dip your toe in the water with YouTube interviews, then you can listen to Kemple give an introduction to realism or lead an excellent introductory discussion on semiotics and realism.

To be sure, the effort that Kemple is inviting others to join is not for the dilettante. It requires a fair amount of focus and commitment to unlearn our anti-realist habits and learn the principles by which we can defend our common sense and also avoid its pitfalls when the occasion demands it.

But I believe the effort is quite worthwhile, particularly for physicians: Isn’t it an embarrassment that we can’t give families a cogent answer as to whether their brother, mother, or child is alive or dead, human or simply “tissue?”

Economists too could use a good dose of realism and, of course, lawyers, legislators, and those involved in politics should get on the bandwagon as well.

But realism is for everybody, really. The progressive era that we live in, that major ideological orientation of the West of the last 150 years, dead-set as it is to give primacy to scientific knowledge and to place the administration of human affairs in the hands of a technocratic managerial class, is necessarily anti-realist. How much longer can we all stand being this detached from reality?

If anyone has any connection to Joe Rogan, I think Kemple would make a great guest on his show.