[I’m preparing my paper for the AERC 2016 and have less time for original content, so I thought I would bring to your attention this editorial I wrote a few years ago. I hope you enjoy it. Figure 1 in this article is my most important contribution to empirical science to date!]

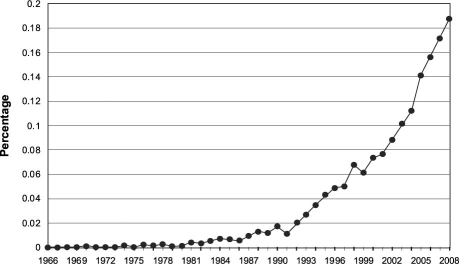

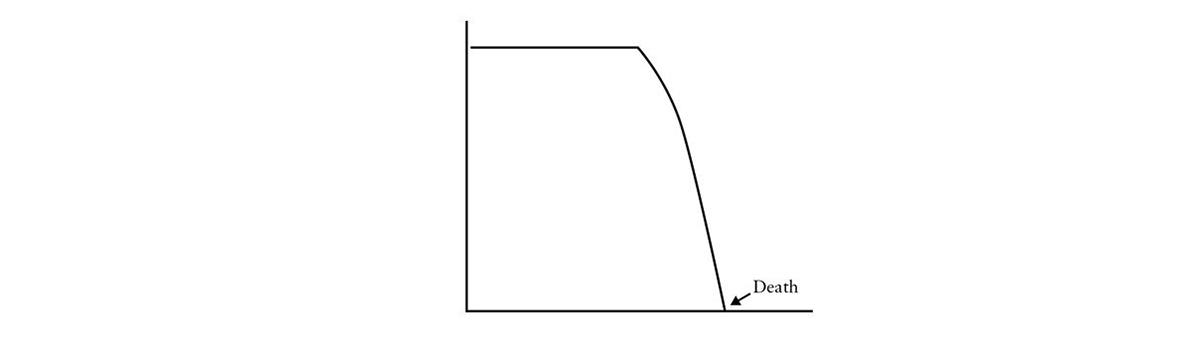

There was a time when the foretelling of future events was an undertaking of prophets, palm-readers, and weathermen. In recent years, however, the medical profession seems to have embraced this activity with a great deal of enthusiasm. A prime example is the use of the term “predicts” in the titles of journal articles dealing with human subjects. According to a search of the MEDLINE® database, “predicts” appeared a total of only 13 times before 1980.1 Since then, however, the occurrence of the term in citation titles has increased dramatically. Expressed as a percentage of the annual number of MEDLINE publications, the trend follows a curve that could be described as hyperbolic (Fig. 1).