I highly recommend listening to our latest podcast with Dr. Vinay Prasad, an extremely intelligent, articulate, and courageous physician who has been absolutely phenomenal speaking out against the “unscientific” public health policies of the last 20 months. Vinay is an astoundingly prolific writer—publishing in academic journals and in the lay press—and now has an excellent YouTube channel that I turn to daily to get his analysis of the latest scientific and health policy news.

During our conversation with Vinay, and reflecting on some outlandish positions taken by the CDC on the incidence of COVID-induced myocarditis, Anish startled me by mentioning Michel Foucault and his notion of “regimes of truth,” the idea that the dominant political forces essentially set the framework under which a society comes to an understanding of things. “If knowledge is not power, but power is knowledge, then scientific objectivity may be a myth. What do you think about that!?” Anish challenged Vinay.

My heart skipped at beat at the thought that my friend had become a full-blown postmodern truth relativist. Fortunately, Vinay stopped him at the brink by noting that myocarditis happens to 12-year-old boys and that there is some objective rate at which it happens, even if people disagree on its estimate or the confidence intervals around that estimate. Take that, regime of truth! Anish wholeheartedly agreed (phew!)

But is myocarditis really objective?

Several months ago, in the context of the controversies about COVID death statistics, I wrote that the diagnostic process is not so much a work of detecting an objective abnormality in the patient but more of a tacit convention among doctors meant to organize our thinking about the varied realities of disease. I expanded on that topic in a series of videos that you can find here. This view of diagnosis relates to the principles of philosophical realism that I broached in my post last week.

Whether modern or postmodern, we live in an era where much of our understanding of the world around us is shaped by scientific modeling rather than by reality. It is not primarily the political regimes, then, that dictate the truth discourse as it were, as much as it is the broad philosophical underpinnings of modernity that inform our political regimes and, secondarily, inform our view of the world.

In medicine, that means that we unconsciously adopt the machine model of the human body whereby we imagine a diagnosis to be a description of a defect either in a part of the body or in the relationships between parts of the body. That view assumes that there is a mechanical standard or “blueprint” of how a human body is supposed to be assembled. Accordingly, to make a diagnosis is to detect and describe a departure from the blueprint.

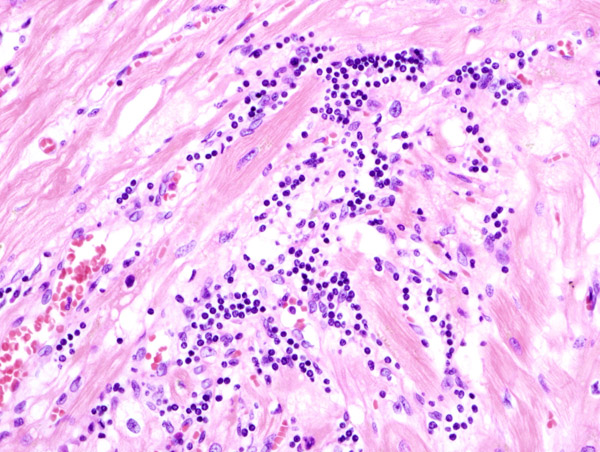

In the eighteenth and nineteenth century, that theory materialized in the practice of autopsy. By correlating autopsy findings to pre-mortem symptoms and signs, the physician could compare the unhealthy body to the healthy one and establish a disease classification on that basis. Later on, the pathology labs and radiology departments would serve as the main diagnostic venues to facilitate this process of detection and description. In that view, “myocarditis” is defined, diagnosed, and detected by the abnormal presence of inflammatory cells in the heart muscle. At least, that’s the theory.

In practice, however, we invariably fail to adhere to that theory for two reasons, one practical and one theoretical. The practical reason is that demonstrating the presence of inflammatory cells in heart biopsies is risky business so we end up relying instead on a combination of surrogate markers of inflammation (constellation of symptoms, electrocardiographic findings, blood tests to detect myocardial proteins, magnetic resonance imaging, etc.), all of which have various problems of sensitivity and specificity for the said inflammatory infiltration.

The theoretical reason is that the theory is wrong. There is no blueprint for the body. The body is not a machine made of parts. The presence of inflammatory cells in the heart muscle does not amount to a disease (after all, there are inflammatory cells even in a normal heart) nor does their absence preclude their being a disease we might collectively call myocarditis. In other words, there is no getting around that making a diagnosis involves a clinical judgment that is irreducible to a set of objective facts.

That clinical judgment, of course, is not arbitrary, at least if rendered well. It is grounded in a “pattern” of being unwell: a set of symptoms and signs that, when clustered together, we call myocarditis. But at the end of the day, a diagnosis is a decision, not the discovery of an objective reality. The primary objective reality is a person who suffers (a patient). What we call myocarditis is a derivative, partially subjective entity, a term of arts.

And I say that “we” call it myocarditis because medicine is a collegial practice. The clinical judgment of the individual physician is informed by the collective experience of other physicians who, together, form the “school of thought” known as Western medicine, itself embedded in the wider context of a modern society’s beliefs about reality and the world out there.

And here lies the crux of what was troubling Anish. After agreeing with Vinay that myocarditis rates are “objective,” he added that the problem is not the diagnosis but “what you do and how you frame that [objective reality] to come up with some policy” that is liable to be influenced by the regime of truth. In other words, ethics and politics.

So here’s the added difficulty: On the one hand, the regime tells us repeatedly that we need to “follow the science” when the science is a nonrealistic mechanical model of reality that cannot be followed unless one also has a sense of reality. On the other, the regime also tells us that ethical principles are subjective, private, and diverse, when, in fact, ethics and politics deal with readily observable realities: human persons and human societies of which we have first hand experience and knowledge.

Anish, Vinay, and I agree that healthy people should not be locked down, that masks should not be required for school attendance, and that vaccines should not be mandated. But we agree on those points not because scientific research hasn’t yet established the cost-benefit ratio of lockdowns, the long term safety of masking kids, or the relative rates of viral versus vaccine-induced myocarditis. We agree on those points based on our grasp of human realities: that the unvaccinated are not a threat, that masks do not belong over kids’ faces, and that locking down is inherently detrimental to the fabric of society.

When I read about the blueprint, I was struck by the idea that it is used to distinguish “normal” from disabled. The disabled do not want to be fixed; they want to be accepted.

Excellent! I wonder, have you considered having Dr Peter McCullough on your podcast?

Thank you, we did https://accadandkoka.com/episodes/episode154/